The Chinese auto sector has been contracting over the past 12 months to June 2019. This persistent weakness has surprised us and markets. Having reviewed the latest data trends and market intelligence from our customers and CRU’s offices in China, we have downgraded our forecasts for 2019 and 2020. There are three reasons why CRU expects China’s auto sector to remain weak in 2019-2020:

- Payback for prior policy stimulus: The ending of the car sales tax rebate in 2018, has reduced auto demand in 2018, but looks to have extended into 2019.

- Uncertainty remains elevated: Chinese policymakers are engineering a ‘managed’ slowdown in China, but it is not clear what that looks like, given the ongoing US-China trade war; such uncertainty is likely to suppress the purchase of new vehicles.

- New (Stage VI) auto emissions standards were effective in many cities from 1 July 2019 and nationwide from 1 July 2020; the new rules inevitably create uncertainty for all market participants, manifested in temporary auto sector weakness.

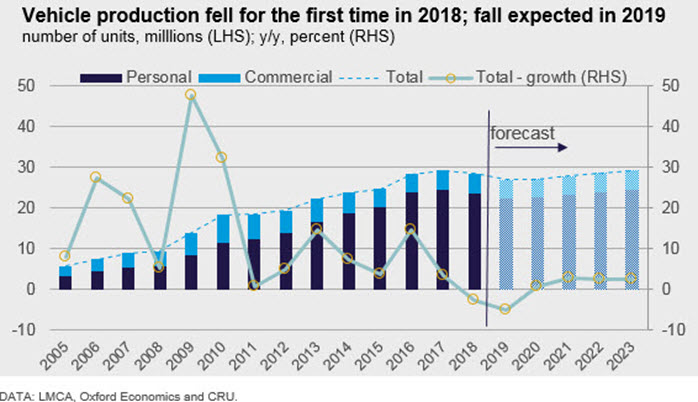

Auto sector has seen a fivefold rise since 2005

The auto sector in China has seen impressive growth in recent decades. Auto production rose from 5.7 million units in 2005 to 28.3 million units in 2018 – a fivefold rise. 80% of the vehicles produced are personal cars, with 20% being produced for commercial use, such as vans and trucks. Every year since 2005, auto sector production has grown. It has grown very rapidly in some years such as 2009 – where production rose by nearly 50%.

The auto sector contracted for the first time in 2018. This is a significant event, given that the sector remained resilient even during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. That makes the recent contraction in the auto sector a real talking point. Auto production fell from 29.1 million units in 2017 to 28.3 million units in 2018. We expect the contraction to continue into 2019 with production reaching 26.9 million units by the end of 2019. We expect the market to remain broadly flat, with 0.7% growth, in 2020. From that low base, we expect modest growth rates of around 2-3% allowing production to rise to ~30million units by 2023.

Why the auto sector will be sluggish in 2019 and 2020

There are three reasons why the auto sector is likely to remain sluggish this year and next.

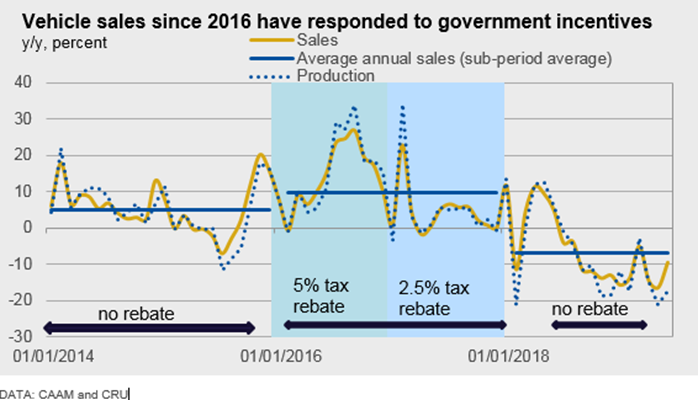

(1) Payback for earlier policy stimulus, namely the 2016-17 auto sales tax rebate

Annual auto production and sales growth fell for the twelfth consecutive month in June. Sales contracted by 17.3% in June compared to a 21.3% contraction in May. Stepping back, it is evident that the pattern of vehicle sales over the past three years has been driven primarily by a temporary tax rebate in 2016-2017 which was available to those buying new vehicles. Following the stock market turbulence of 2015, China provided economic stimulus in a variety of forms including a 5% tax rebate on the 10% car sales tax in 2016, this rebate fell to 2.5% in 2017. Annual vehicles sales growth surged to 26.8% by October 2016, as consumers brought forward car purchases to avail the tax break.

Annual sales growth over the two-year rebate period averaged 10%, twice the rate of growth seen during 2014-2015. We would describe the stronger growth in 2015-2016 as demand that had been “borrowed from the future” – in other words the demand takes place earlier. As the tax rebates ended, the auto sector entered a “payback period”, where the extra purchases that would have happened in the absence of the tax rebates, no longer happens; this means that actual demand in 2018 ends up lower than it otherwise would have been. What is surprising though is that the payback period appears to have persisted into 2019.

(2) Uncertainty on the macro outlook for China dampens auto demand

The Chinese economy is slowing. The economy grew by 6.2% in Q2, the slowest rate recorded since the series began in 1992. The slower growth translates into lower consumer incomes, and a lower ability or willingness to finance a new car outright or to take on additional debt to finance the car.

In addition, there is great uncertainty about the extent to which the economy will slow given the authorities’ desire for slower more sustainable growth, the ongoing trade war, and the activist nature of past government policy stimulus. The key question related to the government’s ability to fine-tune policy to deliver the desired growth rate and successfully allay consumer fears on the trade war.

Economic theory predicts that during periods of uncertainty, consumers tend to cut back first on durable goods, such as a car or a washing machine. That is because the purchase of such big-ticket items is irreversible – and consumers prefer to make these choices when they have greater confidence over a positive economic outlook. While we suspect that these forces are at play in the coming quarters, these effects are hard to quantity.

Our view – which has been affirmed so far - is that the government will respond with stimulus at the margin to stabilise growth, rather than to generate an upswing. For example, the National Development Reform Commission (NDRC) said in November that a nationwide tax cut for car sales was not under consideration; although the Ministry of Finance did announce a technical change in the computation of the car purchase tax, which should reduce costs for most buyers. In June the NDRC enabled local governments to encourage car demand through raising the quota on annual car licences and relaxation of car use in congestion charging zones. While some cities have taken advantage of these policies (e.g. Guangzhou and Shenzhen), others have not (e.g. Beijing). As a result, we assess that auto sector specific policies are likely to deliver only a small uplift to car demand.

(3) Temporary auto sector weakness likely in transition to new emission standards

New auto emissions rules mean that new vehicles can only be registered if they meet the new standards.

Stage IV of the Auto Emissions Standards

What are the new emissions standards?

China’s auto emissions standards mirror those of Europe, sharing a similar numbering system. The International Council on Clean Transportation note that China is about 2 years behind Europe in terms of its implementation of the emissions standards. For instance, the EU introduced its Euro VI standard in 2015, while China introduced the China V standard in 2016. China is now moving to introduce the Stage VI standard.

What is the timetable for implementation?

The new China VI standard is to be implemented nationwide from 1 July 2020. It is being implemented earlier, from 1 July 2019 in 15 cities and provinces including - Tianjin, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing, Chengdu, Chongqing. And the following provinces - Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Henan, Anhui, Hainan, Guangdong, Sichuan.

A lesson from the new car emissions standards introduced in Europe in 2018 Q3 (the WLTP) is that it takes time for all the participants in the auto industry to understand and abide by the new rules. In Europe the new tests simply took longer to carry out per vehicle and were being required for a larger number of vehicles (all model variants rather than just the base model). In Europe this has created a temporary weakness in the auto industry that has lasted at least two quarters. This weakness arises through the following mechanisms:

- Manufacturers will typically face uncertainty about what changes to the vehicle are required, in practice, to meet the new standards. Some vehicle batches may fail the tests, risking a back log in production and orders.

- For most consumers, a car is a major purchase that will be used for an extended period. As new car models become available under the new standards, consumers will need time to familiarise themselves with the options to determine and consider what best suits their future needs.

- Car dealers will want to sell off cars that meet the old standards, through discounts to clear their showrooms. Local media reports suggest that prices of old models are being slashed by as much as 50 per cent. If consumers find these stock clearance deals attractive, it may boost auto sales for a month or two, but it will be insufficient to buck the larger adjustment required to meet the new standards.

Extrapolating from the 2018 European experience, our view is that the new standards will weigh on the Chinese auto sector through 2019H2, with some sluggishness persisting into 2020 when the legislation becomes effective nationwide.

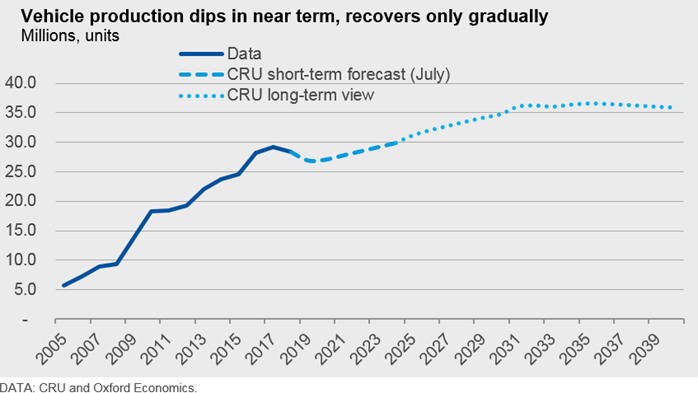

Auto sector challenged in near term; rewards further out

Considering the three factors above we have taken a judgement to significantly downgrade our auto production forecasts for 2019 - 2023.

- 2019 auto production forecast has been revised down to -5.1% from +0.8% in May

- 2020 auto production forecast has been revised from to 0.7% from +5.0% in May

- 2021-2023 auto production forecast revised down to 2-3% from 4-5% in May

As we look further out in time, our forecasts are consistent with the long run saturation rate of car ownership in China. This is determined by trends in the working age population, share of population in urban areas, pollution and congestion policies as well as the total cost of car usage. Based on these factors, we currently expect some further growth in the Chinese auto market - from around 28 million units currently to approximately 35 million units by 2030.

The auto industry in China is currently facing a number of cyclical and structural challenges, some of which are global in nature – e.g. uncertainty around the pace of technological advancement of electric vehicles and related government policies (e.g. with regards to regulation around driverless cars). These uncertainties make it difficult to tell how long the current auto market weakness will continue. We will monitor developments closely over the summer and reassess our view in the Autumn. As the American Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson said, “when my information changes, I alter my conclusions”.

CRU Economics