Rio Tinto and Glencore are again in talks over mining’s most obvious deal, but big questions remain – why now, where do the synergies sit, what hurdles stand in the way, and what could a transaction actually look like?

Glencore and Rio Tinto resume megamerger talks

Mining mergers and acquisitions have started 2026 much where 2025 left off, amid reports that talks have resumed over a potential $260 bn ‘Glen Tinto’ merger. Late on 8 January, both companies issued statements confirming that preliminary discussions are taking place regarding a possible combination of some, or all, of their businesses. While no terms have been disclosed, Rio Tinto has until close-of-business on 5 February to announce a firm intention to make an offer unless an extension is granted.

If completed, the transaction would rank as the largest mining deal in history, and one of the largest ever corporate deals. Current discussions mark the third act in the ‘Glen-Tinto’ saga, following an initial approach in 2014, and a round of talks last year. Recent discussions reportedly stalled over valuation, leadership and Glencore’s coal operations. Dubbed by Glencore’s CEO Gary Nagle as “the most obvious deal in mining”, it raises an obvious question – why now?

Buy over build in the search for copper

In a week when prices first broke $13,000 /t, the logic (like much of the recent high-profile mining mergers and acquisitions) centres on a copper play. Glencore has increasingly positioned itself as a copper growth story, and record prices have only reinforced the structural deficit narrative. Meanwhile, Rio Tinto has been explicit about aligning its portfolio to high-growth energy transition commodities, led by copper but extending to lithium following its Arcadium Lithium acquisition (link accessible to CRU clients - if interested contact us here). Out to 2035, we estimate a staggering 750 kt of additional copper supply needs to be added each year to meet accelerating demand.

The timing also suggests leadership teams are more willing to strike a deal than ever, with many miners seeking to buy rather than build. Rio Tinto appointed a new CEO in Simon Trott last year, while Glencore’s CEO commented that “it makes sense to create bigger companies … to create material synergies, to create relevance, to attract talent, to attract capital”. With that in mind, where would the synergies sit – and just how influential could a combined group become?

Copper and aluminium synergies are most evident

A complete merger would create the world’s largest mining group, involved in more than 20 markets. Strategically, Rio Tinto’s tier‑one mining and processing assets would benefit from Glencore’s global marketing and trading capabilities – raising the prospect of synergies not only from scale, but from route‑to‑market optimisation, risk management and portfolio reshaping.

Across CRU’s basket of commodities, a total ‘Glen Tinto’ merger would comprise over 135 production assets in 26 countries, and would represent a top five producer in bulk commodities, aluminium, base metals, energy transition metals and ferroalloys (analysis uses CRU’s Copper and Aluminium Market Outlook data, among others). This breadth would increase capital allocation optionality, strengthen resilience through the commodity cycle, and preserve copper-led growth. Below we assess the potential impacts for each commodity.

Copper

The merged entity would represent the world’s largest copper miner, accounting for around 7% of current mine supply, controlling a deep portfolio of Tier-1, long-life copper assets and advanced-stage development options (including El Pachon, MARA and Resolution). From a product perspective, the merged entity would be structurally net long copper concentrates. Rio Tinto brings high quality concentrate production, while Glencore’s smelting system would not have capacity to process all of that material and also faces ongoing uncertainty over its operational continuity. Fewer, larger sellers of concentrate would reduce counterparts for smelters, potentially placing downward pressure on TC/RCs through the cycle. In a market that recently set a benchmark TC/RC of 0/0, an increased market concentration of copper intermediates will attract scrutiny from countries that are net importers of copper concentrate.

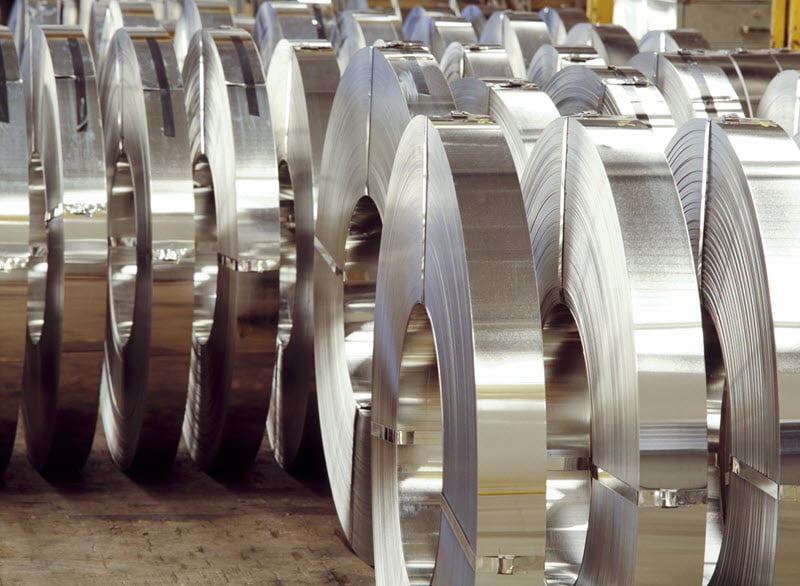

Aluminium, bauxite and alumina

A combined entity would be significant for aluminium, combining Rio Tinto’s position as the fifth largest producer globally in 2026, with Glencore’s scale as a major trader of primary aluminium and alumina (plus bauxite to a lesser extent). Rio Tinto’s key exposure is smelting capacity and technology, concentrated in Canada with additional interests in Oman, Iceland and New Zealand. Glencore has no direct ownership of primary aluminium smelters, but holds a share in the integrated producer Century Aluminium, a 70% interest in the Aurukun bauxite project, and is understood to remain a stakeholder in EN+, which in turn has a controlling stake in the major producer Rusal.

Iron ore

Rio Tinto would provide meaningful exposure to iron ore. Output from its high-quality Pilbara assets, combined with output from the Iron Ore Company of Canada (in which it holds a majority stake) totalled around 340 M wmt in 2025, with almost all of this directed into the seaborne market. This represents a 20% share of seaborne trade and positions Rio Tinto as the largest mined iron ore producer. Rio Tinto also has significant upside via the Simfer joint venture (where it holds a 45% stake) in Simandou South. The joint venture is expected to produce up to 60 million wmt, forming half of the broader Simandou development, which shipped its first ore in November. Glencore has no iron ore production, and its exposure is limited to the El Aouj and Askaf projects in Mauritania, after exiting the Zanaga project in the Republic of Congo in early 2025.

Coal

Rio Tinto no longer produces coal, having sold its remaining assets in 2018, so any merged entity would effectively inherit Glencore’s coal stance. However, Glencore’s coal exposure was reportedly one of several barriers to last year’s discussions. During the acquisition of Teck’s steelmaking coal portfolio two years ago, Glencore also flagged that it could ultimately demerge its coal business, which has since been restructured into a separate Australian entity. While the perceived ESG-related pressure on holding coal assets has eased somewhat recently, softening prices could make a spin-off justifiable on financial grounds.

Lithium and battery materials

While Glencore is less exposed to battery materials, a combined platform could accelerate Rio’s lithium pivot following its $6.7 bn Arcadium Lithium acquisition (link accessible to CRU clients - if interested contact us here) at a time when the market is shifting more towards spot trading. Over the past year, Glencore acquired Canadian battery recycler Li-Cycle, and signed an offtake agreement with Vulcan Energy over lithium hydroxide.

Other markets: Ferroalloys, cobalt, nickel, zinc and lead

Glencore is the merged entity’s only meaningful exposure to these other commodity markets. As a result – and barring divestments – a combination would be unlikely to materially change the structure of these markets, though their relatively small size means they may struggle to compete for capital allocation under a copper-led investment agenda.

Rival bids, valuation and antitrust: The hurdles to a deal

Despite the strategic logic, several hurdles stand between discussions and a completed transaction. In the wake of BHP’s failed pursuit of Anglo American, some market participants have speculated about a potential BHP approach for Glencore – although there has been no indication that BHP is preparing a bid. A BHP-Glencore tie-up would appear to offer less value than a ‘Glen Tinto’ merger given limited aluminium overlap, BHP’s aversion to South Africa (made apparent during its bid for Anglo American), and the likelihood of competition concerns in coal (and copper which would likely persist for either BHP or Rio Tinto).

An all‑share acquisition of Glencore by Rio Tinto is widely seen as the most plausible structure, but valuation could prove a stumbling block. Some investors speculate Glencore would push for a c.30% premium, while Rio Tinto would prefer minimal (or no) premium, implying any agreement would likely settle somewhere in-between. The Anglo-Teck deal suggests that “headline” premia can be diluted by deal structure (including special dividends and other considerations), even when the strategic rationale is compelling.

Finally, regulatory approval is likely to be the decisive step. The Anglo-Teck deal has so far received Canadian approval, which we as a “goldilocks” combination (link accessible to CRU clients. If interested contact us here) – too small to pose insurmountable objections about market dominance, but large enough to defend against further bids from larger peers.

By contrast, a merger combining major positions across copper and aluminium is likely to face multi-jurisdictional scrutiny, particularly in China and the US. Mining’s largest M&A deal to date, Glencore-Xstrata, is instructive – regulatory concerns resulted in asset sales, most notably conditional by China on the sale of Las Bambas (to MMG). Anti-competition concerns aside, select divestments (potentially spanning coal and/or parts of Glencore’s trading business) may be necessary to optimise, with market contacts speculating over potential bulk commodities/base metals, or steel/energy/base metals-lithium spin offs. However, because copper is both the main strategic rationale and the largest regulatory flashpoint, onerous divestment terms could be a deal-breaker. In any credible path to completion, flexibility will be critical.

CRU will maintain close coverage of developments and provide further analysis in due course.

If you are interested in exploring more of CRU’s commodity insights, request a demo here.

Additional contributions from Craig Lang, Alex Christopher, Ian Warden and Jonathan Loh