The COP26 was heralded as a “moment of truth” in the race against climate change. In addition to the expected announcements, such as those on finance, there were also some unexpected ones, such as the pledges from the Indian government to address climate change. The latest pledges, if implemented in full, will bring us closer to reaching the important 1.5 °C pathway – but more needs to be done. While COP26 did not deliver any major breakthroughs, it helped entrench the so-called ratchet mechanism, which will require countries to return with more ambitious climate-change targets in the future. This is a good platform for further progress, starting with COP27 in Egypt in 2022. For the commodity markets, this means the pace of change is set to accelerate as policy, as well as financial, customer and community demands, respond to the growing need for action.

The key takeaways from COP26

COP26, the United Nations’ 26th ‘Conference of the Parties’, was heralded as an important milestone – a moment of truth – in the race against climate change. While UK officials proclaimed the outcome a success, many others concluded that COP26 had fallen short of what is needed to contain climate change.

In this insight we discuss the major announcements at COP26 and offer a preliminary assessment of what mattered most for the commodity markets.

Figure 1 presents the key takeaways that hit the headlines over the last couple of weeks. Some of these were expected – such as the financial markets’ commitment to help the transition to a low-carbon economy – while others were not. India’s pledge to become carbon neutral by 2070 and the US-China climate declaration stand out among the unexpected announcements.

COP26 announcements should contain the increase in global temperatures, but questions remain

The above pledges, if followed with effective domestic policies, could make a significant contribution in the fight against global warming – it could help to contain the increase in global temperatures to ~1.8–1.9 °C by the end of the century. This is significantly lower than the projected increase of ~2.7 °C under current policies or that based on pre-COP26 commitments of ~2.1 °C (Figure. 2).

The latest projections also show a large degree of variation around these estimates. This variation reflects the different assumptions used and scenarios assessed. The International Energy Agency (IEA), for example, provides a plausible range of 1.4–2.3 °C around its 1.8°C estimate. Similar ranges exist around other projections. Put another way, the range of plausible outcomes is far larger than the estimated impact of the COP26 announcements on global temperatures themselves.

Whatever the uncertainty around the long-term projections, the major announcements mentioned above, if implemented in full, should reduce annual global emissions of greenhouse gases by ~9 GtCO2e additionally by 2030. This is the strongest evidence that COP26 has been a step in the right direction. That said, we are still far away from the 1.5 °C pathway.

Looking behind the headlines: what do the pledges and commitments mean in reality?

India going net zero by 2070

One of the unexpected announcements at COP26 came from the Indian government, which made several pledges to address the climate challenge. These pledges involve installing 500 GW of non-fossil capacity, meeting 50% of energy requirement from renewable sources by 2030, reducing 1 bn t of emissions by 2030 and reaching net zero by 2070. However, the terms ‘renewable’, ‘energy requirement’ and ‘emission’ in the pledges are not clearly defined, making the pledges open to interpretation.

With respect to the ‘50% energy requirement” pledge, our analysis clearly demonstrates that this refers to electricity capacity rather than electricity generation as the latter measure would require a much higher non-fossil capacity than the 500 GW announced. Also, CRU calculations suggest that hydro power has been excluded from this capacity pledge. If renewables do lift to 50% of generating capacity by 2030, which itself is a challenge, this would translate into ~30% electricity generating requirements based on our base case forecasts for electricity demand in that year.

Regarding the pledge to reduce the carbon intensity of the Indian economy by 45% from the 2005 level, our analysis suggests that this would equate to a ~1 bn tCO₂ equivalent reduction in emissions by 2030 (n.b. another pledge) relative to the previous 33% reduction target, as long as the Indian economy grows at ~6% per year in real terms over the next decade. We judge this to be a realistic growth assumption.

Regardless of these ambiguities, the latest pledges do not appear to be particularly ambitious with respect to previous targets. For instance, in early-2020, the Indian Ministry of Power had already proposed reaching 519 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030 – although the achievement of 500 GW of non-fossil power is a challenging target. Similarly, the latest pledge to lower the 2030 national GHG emission target from ~6 GtCO2e to ~5 GtCO2e, still a >50% increase over current levels, is only marginally more ambitious than that projected by CRU for 2030 prior to COP26. In that sense, the new target of a 45% reduction in intensity was easy to make, as it was more or less in line with previous ambitions.

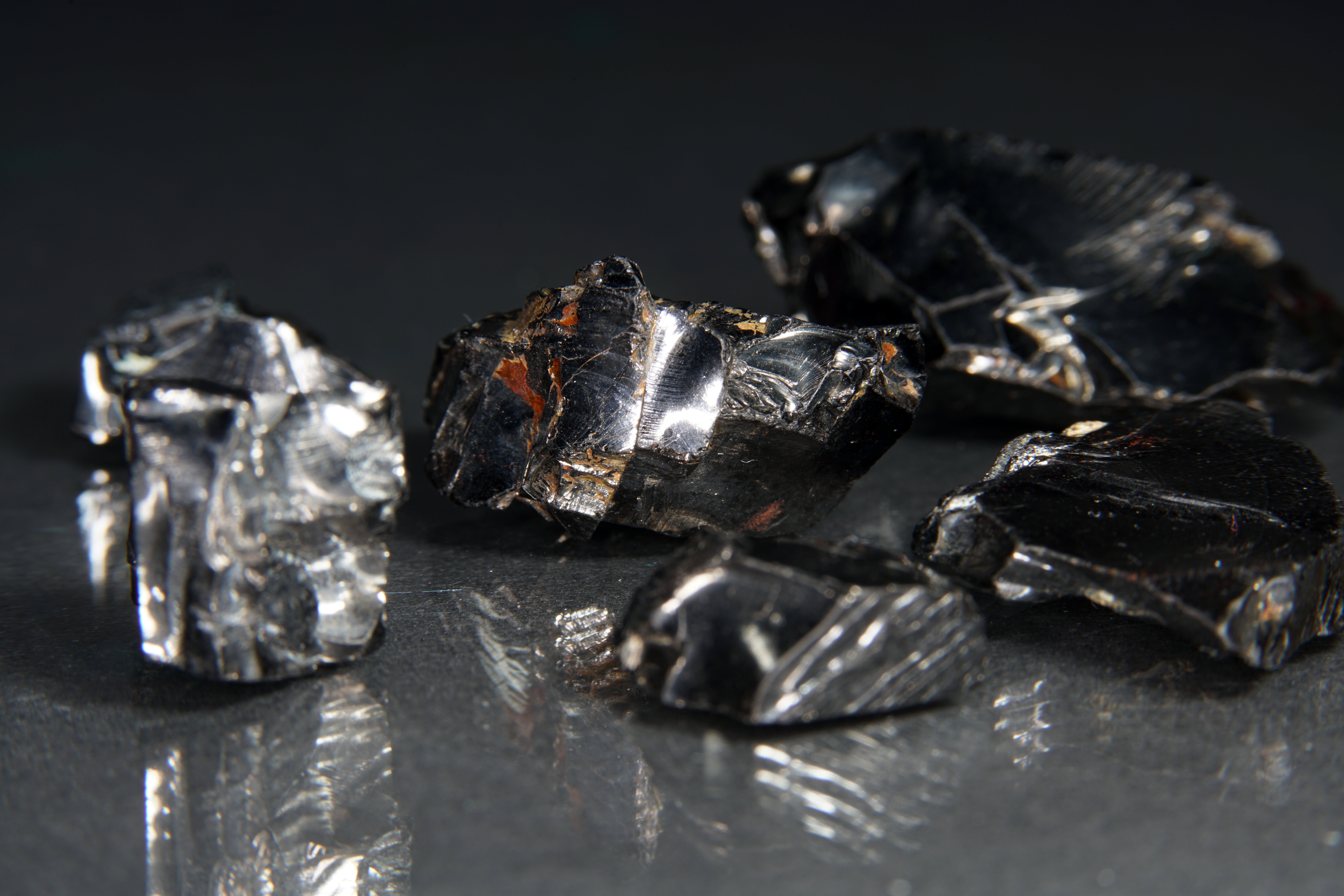

Phasing down Coal

Key pledges made at COP26 impact thermal coal primarily: including pledges by 20 countries to end overseas financing of coal plants; pledges by 69 countries to end coal-powered electricity generation in the 2030s or 2040s; $8.5 bn pledged from numerous advanced economies to South Africa to finance the transition away from coal-fired electricity generation; and lastly, the above-mentioned pledges by India to reach 500 GW of non-fossil power generation by 2030 and achieve net zero by 2070.

Taking an optimistic view of implementation and assuming no double counting across pledges, our analysis shows that thermal coal demand could fall by 15% by 2030, versus our pre-COP base case of a 9% reduction (n.b. equivalent to an additional, annual reduction of ~746 M tCO2 by 2030). While this would represent genuine progress, this is still a long way from the required reduction of ~50% to reach the 1.5 °C pathway (Figure 4).

Methane

Separately, the methane reduction pledge, led by the US government, aims for a 30% reduction in global methane emissions by 2030. Announcements suggest this pledge will focus on high emission and lower abatement cost sources, such as from oil and gas production, and, if implemented fully, avoided emissions could reach up to ~2.8 GtCO2e in 2030. However, this would require a >90% reduction of methane emissions from the oil and gas sectors before 2030, which would require significant upfront investment as marginal abatement costs rise significantly. Alternatively, those countries signing the pledge could look to fund reductions in other countries, providing a greater volume of lower cost abatement options overall, although no such funding arrangements were announced. Various studies – and our high-level calculations – suggest the average investment cost to abate the entirety of emissions from the oil and gas sector might be of the order ~$500–1,000 /annual t methane abated, suggesting significant funding requirements to reach full abatement.

Less optimistically, if the pledge only covers emissions from countries that signed the pledge and only a 30% reduction from oil and gas in those countries is achieved – which would focus on the most economically recoverable methane – then the fall in CO2 equivalent emissions could be as low as ~300 Mt by 2030.

The unexpected US-China announcement on closer co-operation could add a further 25 MtCO2e reduction if applied fully to the oil and gas sector in China, however, the coal sector is a larger emitter, at ~560 MtCO2e, and is likely to be the focus of efforts there. In fact, CRU’s base case view of coal production in China already implies a potential reduction of methane emissions from coal production of 20–30%.

Finance

As expected, the capital markets played an important role at COP26, with more than 450 market participants from banks, insurers to asset managers and service providers, such as rating agencies, came together under the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) (n.b. see our previous insight Climate change: it is (nearly) all about money). These market participants, which together hold assets under management (AUM) in excess of $130 tn (i.e. approximately one third of the global capital markets), committed themselves to financing the energy transition over the coming decades (Figure 5).

With more members and assets under management than prior to COP, GFANZ appears to have momentum. The commitment itself, though, says little about how much capital will be deployed to green causes or by when. For a start, the headline $130 tn should not be interpreted as being entirely available for green activities; it merely represents current AUM of GFANZ members. Even if it were, would it suffice to finance green investment over the next three decades? And how quickly do GFANZ members intend to move their financing towards green activities? COP26 did not provide explicit answers to these questions. Instead, market participants emphasised the need for an operating environment that allowed them to manage their risks and keep financing during the transition. Such an environment would require policy predictability and further progress on financial disclosures and standards. While policy predictability cannot be taken for granted, we expect progress on disclosures and standards. Indeed, a new International Sustainability Standards Board was announced at COP26 just for that purpose.

What does COP26 mean for the commodity markets?

For the commodity markets there are several other takeaways from COP26 beyond the direct impacts on coal already discussed. Any accelerated shift towards renewables, as implied by the announced pledges, would be relevant across several commodities as renewable electricity is highly material-intensive. For example, offshore wind requires 8–10 times more steel per MWh generated than gas-fired power, while the cabling requirements of offshore wind farms and high-voltage direct-current power lines are a key driver of copper demand. Moreover, the agreement to end fossil fuel-based vehicle sales by 2040, signed by 24 countries and leading car manufacturers, seems likely to accelerate the shift to electric vehicles, again driving copper, but also battery metals, demand. Finally, the opening of, at least, six ‘green shipping lanes’ by 2025, announced by a coalition of 19 countries, could see accelerated deployment of low-carbon fuels, such as ammonia.

Thus, among the hot air there was also genuine progress at COP26. If implemented, the new announcements could contain the increase in global temperatures to ~1.8–1.9 °C which is much closer to the 1.5 °C required than what was projected prior to COP26. Moreover, in our view, COP26 established the foundations to make good progress in the future, including by entrenching the so-called ratchet mechanism, which will require countries to return with more ambitious climate-change targets in the future. As such, it offers a solid platform to make further progress, starting with COP27 in Egypt next year.

Taking this into account, a main message to take away for the commodity markets is that the pace of change in this area will certainly accelerate, even beyond that experienced over the last two years. This is going to create uncertainty while policy developments, as well as financial, customer and community demands, respond to the growing need for action.

Continuing the conversation, our team hosted a roundtable session covering the key takeaways from Glasgow. Click below to watch the on-demand webinar, COP26: Real progress or more hot air?