On 25 May, the Trump administration launched a Section 232 investigation to determine whether imports of vehicles and car parts are a threat to US national security. The president is proposing a tariff of 25% on those imports in the future and whilst this is a significant hike from the current 2.5% tariff on imports, it is similar to the existing 25% import tariff that the US has levied on pick-up trucks since 1964.

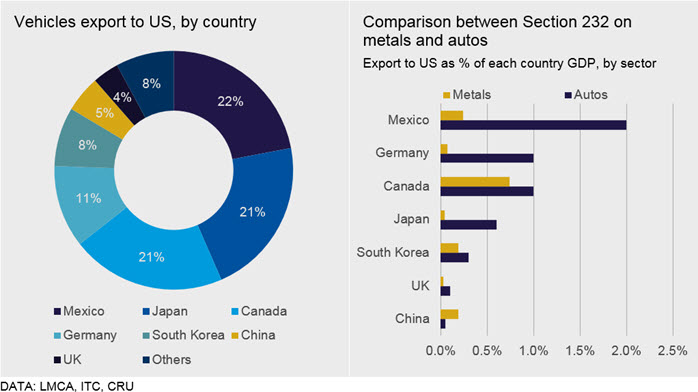

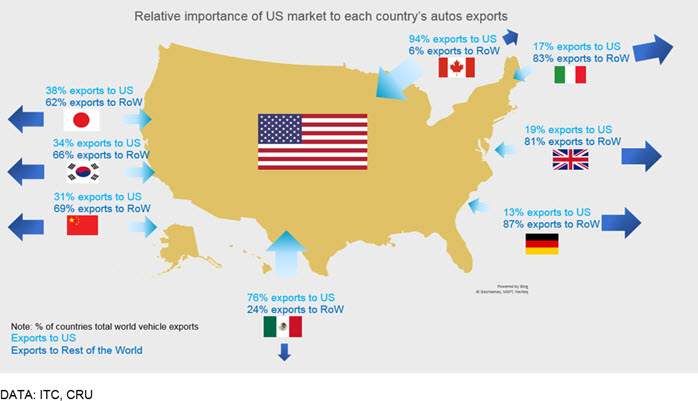

This investigation into the vehicle sector truly strikes at the heart of EU and Asian exports to the US. Although the impact of tariffs on the US economy will take time to be fully realised, the impact on exporting partners would be more immediate because America’s demand for vehicles will be difficult to replace in the near term. In 2017, the US imported $225 bn of vehicles and parts from 161 different countries. Of this, there are seven major countries whose combined exports to the US account for 90% of all imports in these categories. They are, in order: Mexico, Canada, Germany, Japan, South Korea, China and the UK. Earlier this year, a similar 232 investigation into imports of steel and aluminium resulted in the introduction of a 25% tariff on steel and a 10% tariff on aluminium. With the exception of China, the potential tariff on US imports of vehicles and parts would hit these countries harder than the Section 232 on aluminium and steel, as shown in the charts below.

US vehicle tariffs are a Demolition Derby with no winners

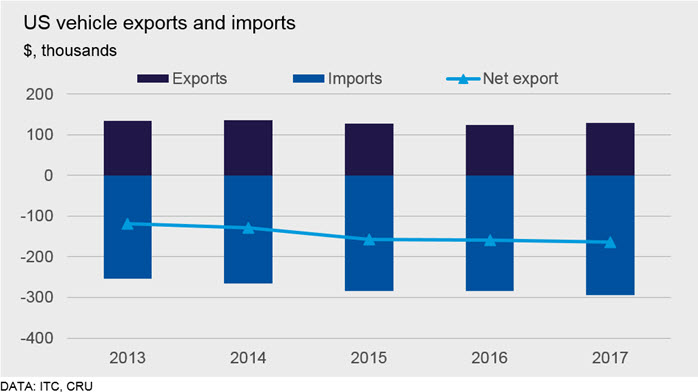

The US relies heavily on imports to meet vehicle demand and imports far exceed exports. In 2017, imports amounted to nearly $294 bn versus just $130 bn exported. Autos account for over 15% of overall US imports, making this the largest category of products brought to US shores. This is much greater than steel and aluminium imports, which were deemed a national threat, as they account for just over 1% of total US imports.

US allies are the trade partners with the most to lose

Given the linkages in the North American supply chain which have evolved since the adoption of NAFTA in 1994, Mexico and Canada would be most negatively affected by the US tariffs. They account for 42% ($105.6 bn) of total US vehicle imports. As neither country is exempt from the steel and aluminium tariffs despite their participation in NAFTA, we cannot assume they will be granted exemptions for the vehicle tariffs either.

About 94% of Canadian-made vehicles are exported to the US, a large majority of which are produced at plants owned by US brands such as Ford and GM. While Canadian vehicles represent about 1% of GDP, roughly three-quarters of Mexico’s vehicle output is shipped to the US, accounting for 2% of GDP. Mexico’s exposure to the US vehicle sector has increased since the country is now home to large vehicle assembly plants owned by US, European and Japanese carmakers. By establishing plants in Mexico, these foreign brands aim to take advantage of lower labour costs and the access that NAFTA provides to US consumers. Toyota, Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, Honda and Mazda all produce vehicles in Mexico and account for 34% of Mexican output. The fate of these plants in Mexico, and to a greater extent, in Canada, rests heavily on NAFTA remaining intact. If NAFTA were to be dissolved, Canadian operations may struggle to find alternative export markets whilst some Mexican output could be redirected to Latin America.

Japan, Korea and Germany are also affected by the tariffs. These countries have production sites located in North America and significant direct vehicle exports to the US. In terms of sales value, Japanese, Korean and German car manufacturers export about $49bn, $20bn and $28bn, respectively, to the US market. For Japan, this figure represents about 0.6% of its GDP. An increase in the tariff to 25%, from the current 2.5%, could lead to an estimated $21bn in lost earnings for Japanese automakers. South Korean producers, such as Hyundai Motor and Kia Motors, may fare even worse, as, proportionally, they export more cars directly to the US. Lost profit for Korean manufacturers is estimated at up to $4.5bn.

Although it is the fourth largest exporter of automotive goods to the US, German companies may suffer less under a tariff regime due to the nature of their vehicle exports. German car exports to the US are worth $28bn per year, the equivalent of nearly 1% of the country’s GDP. However German vehicle manufacturers may have some protection since they supply 90% of the US premium vehicle market. Thus, even if the tariff makes a Porsche even more expensive, the higher price tag is less likely to cause a buyer to switch to a cheaper American alternative. On the 25th July, President Trump and EU officials agreed to work towards a ‘zero tariff’ deal on all imports. This latest move appeared to be an attempt to force the EU leaders to agree to significant concessions on its bilateral trade with the US. Therefore, despite vehicles are being exempted for now, automotive tariff action cannot be dismissed, particularly since the 232 investigation will not conclude until February 2019.

Trump’s plan to ‘make America great again’ will likely hurt Americans

Whilst we have discussed the impact of the tariffs on vehicles, the “parts” aspect of the investigation is a major problem for the companies that have established assembly plants in the US. Much like the metal 232 investigations, it is America’s closest allies that will bear the brunt of this action. Furthermore, if Mexico and Canada are not exempted from the vehicle tariffs, the consequences for the entire North American vehicle supply chain will be widely felt.

Just as we are witnessing in steel, increasing the cost of vehicle and vehicle parts imports and assembly means that Americans will likely pay more for their cars, either through the higher cost of US production or through the higher cost of foreign-made imports.

Explore this topic with CRUThe Latest from CRU

Key takeaways from CRU’s Wire and Cable Amsterdam conference

CRU held its seventeenth consecutive Wire and Cable conference in Amsterdam, during 24–26 June 2024. Day 1 kicked off with a warm welcome to around 200 conference...