The Turkish economy, including its large steel industry, has been affected recently by earthquakes and uncertainty caused by the presidential election. Below we look more closely at the Turkish economy and where it is headed after Erdogan’s re-election.

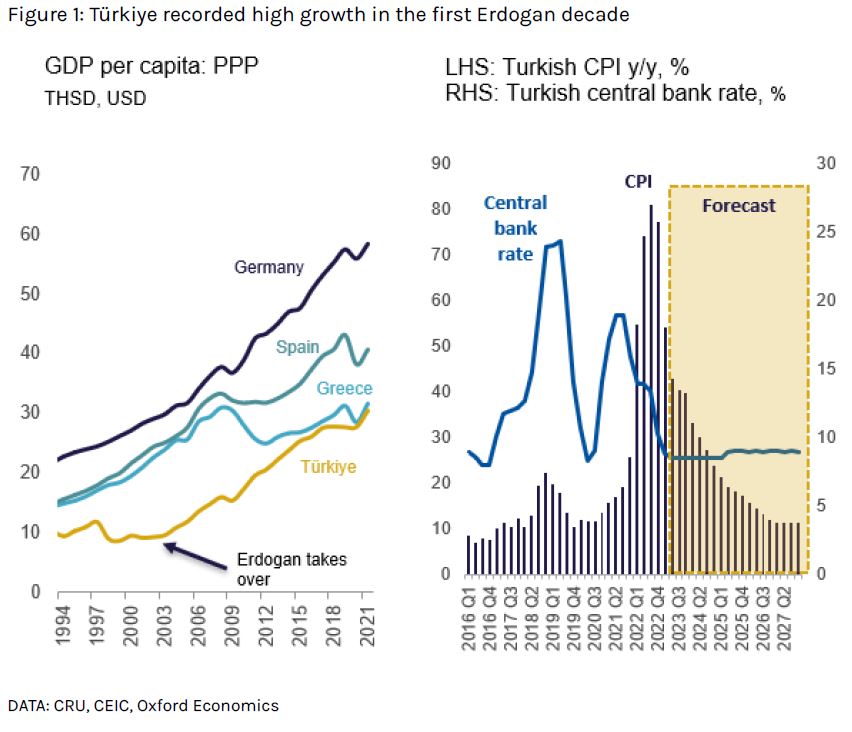

Following the 2001 economic crisis and since Erdogan took office in 2003, the Turkish economy went through a decade of economic boom. During this time, inequality and inflation decreased while employment and wages increased. GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) caught up to levels of some European economies e.g., Greece (see Figure 1). Erdogan’s growth miracle began failing in 2013 with GDP growth slowing down, inflation rising again and a renewed increase in inequality. Erdogan has outlined a new economic model for Türkiye that emphasises growth over financial stability. In 2021 and 2022, loose fiscal and monetary policies combined with strong private consumption led to an annualised GDP growth of 11.4% and 5.5%, respectively, while inflation peaked at 86% in 2022.

Private consumption, which accounts for almost 60% of Türkiye's economic output and grew by 19.7% in 2022, will continue to be crucial for Turkish growth in the coming years. The risk for the Turkish economy, however, is that Turkish consumers have over-consumed in recent months in anticipation of higher prices in the future. Private consumption could therefore lose steam. The Turkish central bank has lowered its policy rate by 50bp to 8.5% in February to stimulate growth following the devastating earthquakes. During the election campaign, Erdogan made it clear that there will be no change in this economic policy and hinted that interest rates could be lowered even further. We therefore do not expect the Turkish central bank to substantially raise interest rates in the medium term (see Figure 1).

While growth was robust, the Turkish economy struggled with high inflation. This was on the one hand due to global supply shortages and the energy crisis but also boosted by the loose monetary policy and a weakening lira. In contrast to most economies, the Turkish central bank started to cut interest rates while inflation was still rising. Due to high base effects as well as falling energy prices and new lending rules, inflation in Türkiye has gradually declined. However, bringing inflation down to single digits will take time and likely require tighter monetary policy. Given the significant increase in the minimum wage and pensions, a 45% wage hike for public sector workers, the continuation of loose monetary policy and weakening of the lira, we do not see Turkish inflation falling below 10% in the coming years.

The stability of the lira is another major concern for the Turkish economy. The lira has lost massive value against the dollar for more than a decade. In 2021, the lira lost 44% of its value against the dollar and 30% in 2022, mainly due to interest rate cuts by the central bank. Leading to the election, the Turkish government has attempted to stabilise the currency through central bank intervention and a series of government programs that made it more difficult to hold foreign currency. Further, the country's foreign currency and gold reserves fell further before the elections as a result of the efforts to stabilise the economy and currency. While this worked for some time, the currency depreciated further right before the election and extended its slide to new record lows following the final election round. We expect the lira to depreciate further in the medium term with narrowing room for emergency measures due to the low levels of reserves.

The weak lira is also exacerbating Türkiye's current account deficit and external debt. Türkiye's current account deficit widened 43% year-on-year in January, reaching the highest monthly level ever recorded. Türkiye's stock of short-term external debt has increased to $203.3 billion through March 2023. Total external financing needs amount to about 25% of GDP. The high external debt increases the burden on Turkish companies and may slow down investment. Companies in the construction sector are particularly vulnerable, as they have no natural hedge against currency risks.

The Turkish economy had a strong start to the year but was then hit by the earthquakes which will negatively influence growth in the short run. The damage caused by the earthquakes is huge and estimated to be above $100 billion by the UNDP, representing more than 11% of Türkiye’s 2022 economic output. However, with government reconstruction efforts, we believe that the effect on annual GDP will be below 1% and the construction sector will benefit at the expense of industry. Türkiye has managed to place itself in a relatively favorable geopolitical position where it can benefit from easy access to the single EU market, has recently experienced a sharp increase in trade with Russia and maintains close relations with the Gulf states, which recently helped to increase Türkiye’s foreign exchange reserves. While big downside risks remain, we expect the Turkish economy to slow down to 1.6% y/y GDP growth in 2023 and bounce back to solid growth of around 3% in the following years.

These and other economic developments that impact commodity markets are discussed with CRU subscribers regularly. To enquire about CRU services or to discuss this topic in detail, get in touch with us.

CRU experts discussed the impact of the war in Ukraine on commodity markets in a recent webinar. Experts from all major commodity areas joined CRU’s Head of Economics and an energy specialist to discuss markets one month on from the invasion of Ukraine. The webinar is available to watch on-demand here.

Explore this topic with CRU